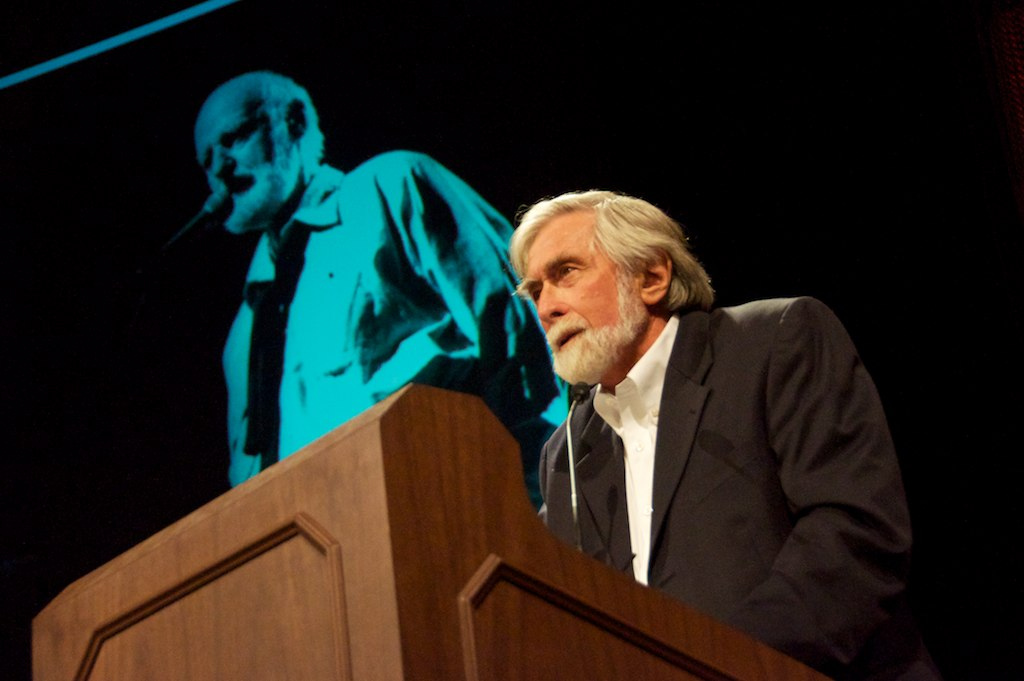

Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Robert Scheer on the Importance of Not Selling Out (Video)

The Truthdig Editor in Chief talks with his lifelong friend, the legendary poet who just turned a 100 years old. http://litquake.org/events/barbary-coast_ferlinghetti

Litquake continues through Oct 9th

http://litquake.org

http://www.citylights.com/ferlinghetti/

http://www.citylights.com

http://litquake.org/events/barbary-coast_ferlinghetti

Litquake continues through Oct 9th

http://litquake.org

http://www.citylights.com/ferlinghetti/

http://www.citylights.com

Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer talks with his lifelong friend and legendary poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who just turned a 100 years old. The two discuss a host of topics, including the importance of not selling out and the founding of San Francisco’s landmark City Lights bookshop.

“What Lawrence represents is the ultimate uncompromising spirit,” Scheer says, “not in the sense of some pompous asshole who says, ‘I know the truth and here it is,’ but in the sense of saying, ‘I am a bullshit detector … whose main concern is that the average person and artists and poets and everybody not get fucked over.”

Listen to their full discussion in the video above. You can also read a transcript of the interview below.

Stephen French: Hello. My name is Stephen French. As part of our ongoing feature documentary on Robert Scheer, we had the opportunity to conduct an interview with Robert and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. In honor of Lawrence’s hundredth birthday, we wanted to share the audio recording. These two friends discussed the changing face of San Francisco; being mistakenly involved in the JFK assassination; meeting Castro; and, most importantly, the uncompromising spirit of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and the ambition not to sell out. Special thanks to Cody Moore, Michael and Doug Poor, along with writer and teacher Laurie Tellic, whom you will hear occasionally in the recording. This took place at Lawrence’s home in late 2018.

Robert Scheer: I’ve read everything with Lawrence, I’ve been around the Beats, and the, you know, hippies and everything. And I had an insight today. What anarchism was was never really a coherent view of how to seize power and maintain it and make life better for people. What it was, what it is, is a cry for justice, a cry to alleviate pain, a cry of desperation that has expressed itself throughout human history. In every culture there are people who say, “enough,” or “this thing, this sucks.” And they do it more poetically, they do it more energetically. They can do it in the name of religion; you know, they can do it against religion. They can put any political label. But what Lawrence represents is the ultimate uncompromising spirit. Not in the sense of some pompous asshole who says I know the truth and here it is, but of saying I–I am a bullshit detector. And I am a bullshit detector whose main concern is that the average person, and artists and poets and everybody, not get fucked over. But the average person; he’s never been an elitist. It’s never been high poetry. That’s the whole urging of Beat poetry: to be urgent, to be accessible, to convey strong emotion, to be uncompromising. That’s what the Beats were about, that’s what City Lights Books was about. Here you have a bookstore; you’ve deliberately stocked it with the world’s literature–not all the literature, but all the literature you feel is honest and worthwhile and commands attention, crosses political lines, crosses stylistic lines, crosses religious lines. And then people forget what a bookstore does that Amazon can’t do, what a library does, with the modern technology. You go over to that bookshelf, you’re looking for the book that somebody told you about, but you see all these other books. And there’s a table there and a chair, a couple of chairs. You don’t have to buy the book. No one ever got kicked out of City Lights for occupying a chair and not buying a book. No one ever did. Lawrence was hell on wheels on that, you know. And in fact, he didn’t say it here, but I can tell you, if somebody couldn’t really afford the book, we let them take it, and hopefully they returned it.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: Well you know, when we opened City Lights Bookstore in June 1953, we fell into a storm of politics in North Beach. Because North Beach was practically all Italian, and a lot of the Italians were anarchists, Italian anarchists. Which was an honorable tradition, being an anarchist. And the others were Mussolini followers. [Laughs] And then, so we opened up City Lights Bookstore right in the center of this whole ferment. And it seemed like all the Italians in North Beach were involved in it. For instance, the garbage truck used to pull up in front, and the garbage man would rush in and buy their anarchist newspapers. We had two anarchist newspapers, published in Italy; one was called Umanità Nova, and the other was–well, I forget what the other was. Two anarchist papers in Italian, and the garbage man would come in and get it. And they were part of the mix, with what was going on in North Beach. And then there–it seemed like there was a ready-made ferment of poets and writers and bohemians that hung out in the cafes, in the Cafe Trieste. And City Lights became a magnet for the poets. I noticed when I came to town, all the bookstores in town closed at 5pm on Friday, and they didn’t open on the weekends. And there was no place, there was no locus for the literary community to congregate. There was no locus for the community. There was what was called the Berkeley renaissance, and they were kind of wandering around, from my point of view, out there in the provinces. [Laughs]

SF: London should have that focus, you know; New York should have that focus, I don’t think it has–

RS: Well, there was a bookstore in Paris, because I went there. Was, what–

LF: You mean Shakespeare and Company.

RS: Shakespeare and Company.

LF: My oldest friend, George Whitman, founded it. It’s still going; his daughter Sylvia is running it. In London there was Better Books. Better Books–Better Books was run by Tony Godwin, who later became the editor in chief at Penguin, and then was fired by the lord who owned the company.

RS: You know, you just answered a question I’ve had in my mind for all this time. Why did–Penguin published our Cuba book. First it was Grove Press, and then Penguin, when we added a chapter about the missile crisis.

LF: Yeah.

RS: And they brought out a worldwide edition–that’s when the book took off. And it was that guy, Tony Godwin.

LF: Yeah.

RS: Anthony Godwin.

LF: Well, he was fired shortly thereafter. [Laughter]

RS: That’s right. And I met him through–

LF: Penguin was owned by some, by Lord somebody, and even though Tony was supposed to be, have a lifetime appointment at Penguin, he was fired for publishing books like the Cuba book.

RS: By the time the book was out with Penguin, I was in a position to make sure it was prominently displayed, because I was a clerk. [Laughter] I didn’t have to ask him, I’d say, you know, I would tell people, come in, yeah, and you might want to buy mine over there. You know, so I can go get some Chinese noodles, you know, with the royalties.

LF: I think that was after you were–when you weren’t working there anymore.

RS: No! The book–you got the years a little screwed up, Lawrence. I was there in ‘63, when Madam–’64, Madame Nhu came to San Francisco. I organized a demonstration down at the Sheraton Palace against her, from your store. I put up posters in your store. And you supported it. And, ah–

LF: Shig wouldn’t have posters.

RS: And I think when Kennedy was shot, I was getting my hair cut across the street at some barber shop. And I remember I came in the store and somebody said the FBI’s looking for you, because they say you’re a member of an organization that killed the president. It was Fair Play for Cuba. And I said oh, no, no, I’m in a group called Students for Fair Play for Cuba. But I remember that, it was very–I walked across Columbus, came in, I think Shig or somebody said hey, the FBI’s trying to get ahold of you. [Laughter] You know. And I had to clear that up quickly, that I had not killed the president. But you–I found a home at City Lights. And that’s where I started doing my Vietnam stuff, and then I went to Vietnam and everything. Because you got it right away. You were part of a post-World War II generation, at least some of you, that knew even the good war was a horror.

LF: Yeah.

RS: That’s, I would like–so for me, that was the confirmation, it was the–

LF: Well, it was only until, it wasn’t–it was in the 1960s that I realized that. Up to then, I was a good American, and I thought the war was wonderful. I was totally politically naive, and I didn’t really have any political education until I started listening to Kenneth Rexroth on KPFA FM, the Berkeley station. And I got a complete political education listening to Rexroth’s program, and also going to his house, where he had a–he called it a soiree every Friday night, where a lot of the best poets in town showed up. At 250 Scott Street, in the old Fillmore district, when the Fillmore district was black; I’m talking about the 1950s. So Rexroth was really a very important, he was the most important literary person in San Francisco. And he was a great political critic, you know; he was, he believed in a philosophical anarchism. And at these Friday night soirees at his house, I didn’t dare open my mouth for about the first year I went, because he was so far ahead of me. [Laughs] I didn’t really have any political education ‘til I started listening to him. The Beat generation was just Allen Ginsberg. [Laughs] You wouldn’t have–there wouldn’t have been any without him. He created the whole thing.

SF: Jack Kerouac, him as well?

RS: He was the right wing of the–[Laughter]

LF: You know, Kerouac didn’t hang out in San Francisco very much. He didn’t hang out with the other Beats. No, he was home taking care of his mother.

SF: I’m really intrigued with the poetry of that time, though. Because I–you know, I tell my students, you know, that here you suddenly see–because we’ve taught them pre-1900 poetry. You know, the definite meter, the definite rhythm, all the time. You know, what’s the–is it pentameter, is it heptameter–and then suddenly, you get the poetry of the Beat Generation. And they’re–they were completely confused. It’s like, oh–so where’s the meter here, where’s the rhythm? You know–

LF: But in Howl, Ginsberg had his own rhythm, you know. It was a definite rhythm; it wasn’t the iambic pentameter, but.

SF: Can I ask you what made you spread out across the page?

LF: Similar to what was happening in painting. There was a–whole field painting; you didn’t just use the straight line, you used the whole page. In the case of mine, the topography was very well balanced; the whole page was very well balanced, like a mobile or a painting.

SF: Yeah.

RS: I stole money from Lawrence Ferlinghetti. It’s the most shameful thing I have ever done in my life. But it’s like the guy in, you know, Paris who stole money. I was hungry. You know–

SF: But you put an IOU.

RS: I did put little IOUs. I didn’t make them that prominent; I tucked them in the back of the cash register. [Laughter] And then I tried, in good faith, to pay back the money. But I have to tell you, it was–it really bothered me. At the end of the day, somewhere or other, he got his money back. But I was hungry! A buck and a quarter, you can’t live–I’m going to take them to show them what used to be the hotel, now it’s a boutique hotel, 444 Columbus. And, yeah, you know. I was grateful for the job, because it’s the only job I had, and I could read. He let us take home books. You let us take home books.

LF: Oh, yeah.

RS: Yeah. And as long as we didn’t mess them up, you could bring them back and sell them. And then he had–you have to understand, you’ll see it when you go to the store–all these great magazines. So that the garbage collector grabbing his anarchist publication was not the only one. You know, we had the only homosexual literature–

LF: It’s true, yeah.

RS: Only, only homosexual–because there was a little guy with a bald head. Remember him? He had the Mattachine Society.

LF: Yeah.

RS: And this is important in the whole gay movement, I’ll tell you. The Mattachine Society was like one of the first. And then we had, who was it, Genet came by the bookstore.

SF: Jean Genet?

RS: Yeah.

LF: What years did you actually work at City Lights?

RS: Well, this is what I’m–I came out–I know very clearly, because you were one of the first people I went to visit. And you remember my wife Serena, who ended up living in your cabin with Lou Embry, who was one of the poets. OK, so Serena and I came out on a Greyhound bus to Berkeley to go to–I was going to graduate school, and she went to work at the Oakland Tribune. She was a journalist, one of the first women to go work at this right-wing, republican newspaper, or any paper for that matter. And the first thing we did, we were there–coincidence, we were able to rent a house for 50 bucks a month that Allen Ginsberg had lived in. We thought we’d died and gone to heaven, OK. I mean, wow, how did–in Berkeley, how did this happen, on Francisco and Milvia. Francisco Street just above Milvia. Little house, not there anymore, behind another house, little wooden house. And the next day, we went over to San Francisco to City Lights Books. That was the mecca; everybody did it. I mean, not everybody, but anybody who got a, had a half a brain. Berkeley was boring; Berkeley had a loyalty oath; Berkeley had an anti-communist purge of its faculty. And most, you know, many of them were gutless; they signed this loyalty oath. And so the action was over at City Lights Books. Now I’ll ask you a question. When did you write [One] thousand fearful words for Fidel [Castro]?

LF: After I came back from Cuba. I was in Cuba in 1960.

RS: But what time in ‘60, what part of the year?

LF: The first, the very first part of 1960, in January, I was in–

RS: OK, so you were–you were ahead of me. So he wrote [One] thousand fearful words for Fidel [Castro]. You should understand, the literary publication of the Cuban communist paper, right, on Monday was Lunes de Revolución. It was the literary page. He was a hero. It was a contradiction. Here is Castro coming in, he’s got some authoritarian tendencies there. Part of it was even anti-sexual, because their antagonism was that Batista had turned, and the U.S. had turned Havana into a whorehouse of decadence and everything, OK. He was a good Catholic boy who, you know, was offended by some of this. On the other hand, he was backed by the revolutionary directorate, students in Havana, and so forth, who said hey, there’s this revolution, we are free, free at last. And they had this literary thing; they also had a film industry. And they embraced the Beats as their heroes.

LF: Yeah, they published them in their Monday literary supplement to the big newspaper, Revolución. It was Lunes de Revolución, Monday of–Monday was their literary edition. And so when I–

RS: Yeah. Everybody read it, you know, people out in the countryside, everyone. It was not some little publication.

LF: When I arrived in Cuba, I didn’t know anybody–I was visiting, I was tracing down my mother’s ancestors, who were Sephardic Portuguese. And the family had come through the Virgin Islands, and my mother’s ancestors filled the graveyard in St. Thomas. My wife Kirby and I went across to Cuba after we were in St. Thomas. We just stopped there; there was no law against stopping there. This was like January 1960. And I stayed at a waterfront dump hotel. There was two guys at the bar, two young guys; it turned out they were young editors on Lunes de Revolución. And so I started talking to them, and they said would you like to meet Fidel? Well, I said, well, sure. So they took us to, took me to a cafeteria, and Fidel came out of the kitchen smoking a big cigar. He shook my hand, had a very soft handshake. He was very friendly. And he just went–he shook my hand, then he went out and got in an open Jeep with no guards, and drove off by himself. Because it was a time of revolutionary euphoria. That period was–he could do no wrong. And he was giving huge speeches that lasted seven or eight hours in the Plaza de la Revolución. At least once a week he was giving these huge speeches, with thousands of people standing there the whole time listening to him. He was a–a fascinating speaker.

RS: So you should understand, this is a year after the revolution; the revolution was January of ‘59, OK. All right. So after Lawrence has been there, and he’s written [One] thousand fearful words for Fidel [Castro]–which was really an incredibly accurate prediction of what would happen. You know, after all, U.S. policy for the next three years was designed to kill Fidel–or actually the next 30 years, 50 years, still going on. OK. So you have this contradiction that you have this literary quarterly, which was a hotbed of poets, writers, gay people, everything, all more motivated by the American Beats than any other thing. And now is their chance–you know, Pablo Armando, Edmundo Desnoes, I forget all their names.

LF: Oh, Pablo Armando Fernández.

RS: Yeah. Yeah.

LF: Yeah.

RS: And, ah, Edmundo Desnoes, I remember–oh, who was the guy who–the editor of the paper, he went to, he took exile in Italy. Not Carlos Franqui. We go down there, and we check this out, and I was aware of all these contradictions. And I by then had already visited City Lights, spent a year in Berkeley. Come back, and I’m in this place called the Center for Chinese Studies, which is a CIA-connected operation to learn Chinese and be economists. And that’s when I get involved here with this guy Maurice Zeitlin, who was a Latin American specialist, and a sociologist who was just getting his doctorate. And we write, we’re giving these speeches; he’s over there one day, hears the speech, and asks us would we write a book for him. Which he doesn’t publish, because he thinks it’s too scholarly and too many footnotes, and–right? He didn’t like it, right?

LF: Yeah. [Laughs]

RS: Yeah, he didn’t like it. But he hooked us up with Grove Press, and Penguin, which I learned again today for the first time the connection.

LF: Well, no, I said–it’s not that I didn’t like it. I–I told Bob, he wrote like a graduate student.

RS: City Lights was the mecca. This I’m not exaggerating. This was for the whole country. You could be sitting there in Toledo, you wanted to get to–the whole thing, being a clerk at City Lights was great because you’re like to conductor at Grand Central Station. People would show up–hey, where’s Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and where are those books? And you know, and if they were good-looking–oh, hey, we’ll go have a coffee after at the Trieste and I’ll tell you all about it, how it works, you know. And it was great. And you know, one of them that showed up one day was Bob Dylan. You know, and he was a big–Lawrence challenges this story. My memory of the story is that Bob Dylan came in with these guys from Minnesota that he knew, that I knew. And he said he was looking for Lawrence Ferlinghetti, because Lawrence Ferlinghetti was the first person to recognize his talent. He denies it. He said my memory was it was in Chicago, the Gate of Horn, or Horn, where Odetta used to sing–

LF: The Gate of Horn.

RS: Gate of Horn, it was in Chicago. In his memory, Dylan told me, was that he was at some poetry reading, long poetry reading. Ferlinghetti was the headliner. His memory was at the end of this very evening, when no one was listening, he got up to read his poetry. And then he claimed that Ferlinghetti stood up and said this kid’s the best poet of the night, you should be listening to him. That was his–

LF: He was reading, he wasn’t singing?

RS: I’m, you know, now I’m–I’m not getting any younger. You know, my memory’s not as good as yours.

LF: I heard him sing at the Gate of Horn in Chicago.

RS: OK.

LF: And I thought his timing was all off. I said that’s really weird timing. And it was irregular, and slow, and fast. And I didn’t realize that he was turned on, he’d been smoking dope and that’s what made his timing all funny. I was so straight I didn’t even know it. [Laughter]

RS: So anyway, they have these different memories, and he has the idea this guy–

LF: Well, when I was–what I remember about Bob being at City Lights was every night, we’d have a bull session about the Cuban Revolution. And whoever came in, we gave him the whole fidelista argument. And there was one guy named Vincent McHugh, who had been a New Yorker writer before he moved west. And he was from the 1930s generation, the generation which turned against communism as the intellectuals became more and more disillusioned with Russian communism. And so this is what–we couldn’t, no matter what we said, Vincent McHugh couldn’t see past his prejudice that he’d lived through in the 1930s. There was a book by Arthur Koestler called The God That Failed, that delineated all the failings in the way the intellectuals turned against communism.

RS: And because this was the issue, Kennedy, after all, was president; Kennedy got to be president, so now it got confused, because this was the guy we’re supposed to like; he’s a new face thing. And yet he continues this policy–accelerates the policy of planning to attack Cuba and so forth. So it becomes this big, hot issue, and then a few later, Vietnam becomes a big issue. Meanwhile, there’s a civil rights movement developing very early on. And what I’m trying to explain is, for me, all of my previous education kind of came to a boil at City Lights Books. And the connection with you guys, being veterans of actual war, my feeling is that Lawrence played–he provided safe haven [Laughs]. People would come through who were draft resisters, were quitting the army. I remember this, you know. They would be disturbed about–some of them were hostile to the books, some were angry that we were against the war. I had a fight with–I don’t know if you remember, I had a fight with a guy downstairs who was pissing on all the books and everything. And he was a veteran or something, and I had to go down and restrain him, and we got in a fight, the cops came and the whole thing. I remember that because there was a guy named Saul Landau who did the San Francisco Mime Troop and another thing. And he was upstairs, and he hears this ruckus, and I’m fighting with this guy on the floor who’s pissing on the books. And Saul comes down, and I say Saul, call the fucking cops! And then Saul says, you think we should? You know, because the cops were not–

LF: Well, we had a policy never to call the cops.

RS: Never call the cops. But I’m–the guy is fucking pulling my hair and punching my face, you know. [Laughter] Yeah, yeah, we are going to call the cops, this guy is crazy! You know, he’s going to kill me! So, it was that kind of a place. But the thread I want to get back to is for me, Lawrence represented the true meaning of sophistication. Now, he’s going to hate to hear this. But the fact of the matter is this guy, who played like he’s just a yokel, actually already had a doctorate, understood French literature, had been in a war, had been at Nagasaki after the bombing, dropping the atomic bomb, had seen all this stuff. And let he’s still playing at being naive. You know, just walking his dog Homer–

LF: I wasn’t playing at being naive, I was naive. [Laughs]

RS: Well, not about French literature. Not about war and peace.

LF: Well. Well, anarchy was a way to liberate oneself from the military-industrial perplex. That’s how it appealed to me. Later on, I realized anarchism could never work, because the population of–when anarchism had its strongest day was when there were less than half the number of people on earth as there are now. So now, it’s just–it’s just too many people on earth to be able to exist without some kind of government. Gradually I evolved, got a long way from anarchism. I became a democratic socialist. Democratic socialism is the future. The younger generation wants socialism, the younger generations in this country. Bernie Sanders made a big mistake: he muted his socialist message when he ran for president. He didn’t really get into it, into the theory and practice of socialism. He’s just trying to be a democrat.

RS: So let me ask you about getting older, Lawrence, because I’m a protégé of yours. These guys are making a film. And you know, I’m 82 years old. I just interviewed Sy Hersh on this podcast; he’s 81, you know. And I–and the big lesson that I got out of my interview with him, and reading his book and all that, the big issue for us goes–and it goes back a lot to the Beats. It’s not about anarchism, it’s about not selling out.

LF: Yeah.

RS: The good thing about an anarchist–it used to be the good thing about a Trotskyist, too, I used to say: they had no country that they had to apologize for. Whatever country was there, that you could count on the Trotskyists to condemn it, you know. And that’s why Che Guevara left Fidel. That’s why Che–Che Guevara was a Trotskyist, and an anarchist of sorts. And Che Guevara ended up being killed in Bolivia because he was going to continue permanent revolution, the same way Trotsky was talking about it. But it all has to do with integrity. Boring word, I know. But if this documentary these guys are making–and I don’t know, these guys could be the CIA for all I know. [Laughter] And fuck us all over, but so what. Yeah, I’ll retain it, you know. And they, oh, they work with the Brits all the time. But leaving that aside for a minute, the real thing I would like to get at, and why I’m wasting your time, maybe, here, is for me you’ve been–and I’m not blowing smoke here–a center of integrity. So whether I was stealing money from your cash register, or I was denying the logic of your message of a thousand fearful words for Fidel, or your anarchism, you were always trying to figure stuff out in a very principled way. So Lawrence, you know, this is my last question. We live in a very changed world. We don’t even have bookstores anymore, or very many of them. We don’t even have books very much; we don’t even know if we’re going to have newspapers. And I think if there’s any value in having these interviews, there’s something about you that I would like to bottle and pass on about integrity. Integrity. Not selling out. And as I recall, the main thing around City Lights and everything was: don’t sell out. Don’t become like them.

LF: Yeah.

RS: That was the main message.

LF: Yeah. And Shigeyoshi Murao, who was the manager of the bookstore, he was very important in that line. Because he–he was someone that his very presence, you got the idea that this was someone who would never sell out.

RS: Yeah. But the whole idea was, it wasn’t whether you were an anarchist or a socialist–it wasn’t that. It was just don’t fall for the corporate state. The Madison Avenue, the advertising world. And now you look at San Francisco–it’s the center of that world. It’s the center of glibness.

LF: I know. And that horrible sales, Salesforce Tower. The tallest building in the west. It’s a disgusting building, and they had the nerve of calling the building “Salesforce.” [Laughter]

RS: Surrounded by homeless people at night.

LF: Yeah.

RS: Huge encampment. All right, Lawrence, you’ve been very kind. And I think we got it, you know. I mean, the reason I wanted, these guys, you know, they wanted to see you. But I mean, you know, this is the whole turning point of my life. I mean, I was on my way to being an asshole. [Laughter] I was. Really, I was. Anything I can do to improve your circumstance?

LF: No. [Laughs] Nothing can be done about old age.

RS: Tell me about it.

LF: [Laughs]

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.